Wednesday, December 27, 2017

From Useless Rasp to Useful Marking Knife

I have a set of really terrible wood rasps that I bought very cheaply years and years ago. They're bad rasps.

I finally got around to making the flat one a useful tool by cutting it up and grinding off its teeth and turning it into a marking knife.

The only issue with it is that the divots left behind after grinding it flat means that it can't be ground sharp with a single bevel; it has to be beveled on both sides, or else the divots will create notches in the edge. I can live with that, but it would be better made from a very fine mill file or an old chisel.

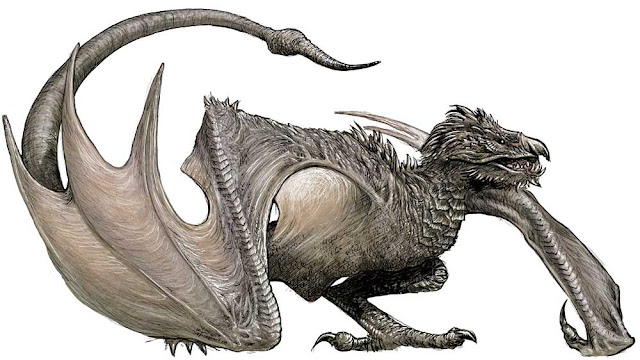

Wyvern

I drew this wyvern for my AD&D campaign journal. It's based on a render of a critter I found on the internet, but unfortunately I don't know who did that original design. I've made my one a bit knobblier though.

It's all been done digitally in Krita, a free open-source paint program that I highly recommend.

It's all been done digitally in Krita, a free open-source paint program that I highly recommend.

Sunday, December 10, 2017

Paper Towel Holder

|

| In all its naked glory |

|

| Fulfilling its purpose |

The base is about 160mm in diameter and 50mm thick, and that much mass of oak is sufficient to create a bit more vibration in the lathe than I've been used to — especially before I realised I hadn't screwed the wood hard up to the face-plate on one side, so everything was turning slightly skewed. It got a bit better after I attended to that, but I don't think my little lathe would be very happy with anything much bigger than this.

Friday, December 8, 2017

Rough-Sawn Macrocarpa Stool

This is a stool entirely for the Outside, that I whipped up in a few hours from a macrocarpa board I found hiding away down the back of the section.

It's very simple, and as far as is possible, without subjecting its users to the dangers of splinters, I've kept the original rough-sawn finish — I've just sanded it down a bit to smooth it off.

I've applied no finish to this one. I'll just leave it out in the weather, and over a couple of years it will develop its own silvery weather-beaten patina.

It's very simple, and as far as is possible, without subjecting its users to the dangers of splinters, I've kept the original rough-sawn finish — I've just sanded it down a bit to smooth it off.

I've applied no finish to this one. I'll just leave it out in the weather, and over a couple of years it will develop its own silvery weather-beaten patina.

Monday, December 4, 2017

Three-Legged Stool

I made the legs for this stool playing around on my new lathe, and they're as long as it can manage in its present configuration, which is about 420mm.

I'm not usually all that keen on staining wood; I'd rather just oil it and let the natural grain and colour come out. But this is made out of low-grade H4 treated pine, which has a rather unpleasant murky grey-green cast to it, so I coloured it to disguise that.

The stool is solid and comfortable to sit on, but aesthetically I think the legs could have done with another few degrees of rake.

I'm not usually all that keen on staining wood; I'd rather just oil it and let the natural grain and colour come out. But this is made out of low-grade H4 treated pine, which has a rather unpleasant murky grey-green cast to it, so I coloured it to disguise that.

The stool is solid and comfortable to sit on, but aesthetically I think the legs could have done with another few degrees of rake.

Sunday, December 3, 2017

Chisel Handle

A friend has loaned me a great armful of turning tools (thanks!), some in dire need of some TLC and others needing little more than a scrub up with steel wool and some sharpening.

I've got some of the rustier ones in a vinegar bath right now, and I used some of the cleaner tools to whip up this chisel handle out of white oak. The ferrule is a copper plumber's gland, the striking hoop is a bit of copper pipe.

I don't actually have a need for a chisel handle right at this minute, but I wanted to practice turning to precise sizes (for the ferrule and striking hoop). I'm doing it at the moment with the aid of calipers, but there's a tool that clamps on to a cut-off tool or scraper that makes the process almost idiot-proof, and I'd like a bit of idiot-proofing.

I've got some of the rustier ones in a vinegar bath right now, and I used some of the cleaner tools to whip up this chisel handle out of white oak. The ferrule is a copper plumber's gland, the striking hoop is a bit of copper pipe.

I don't actually have a need for a chisel handle right at this minute, but I wanted to practice turning to precise sizes (for the ferrule and striking hoop). I'm doing it at the moment with the aid of calipers, but there's a tool that clamps on to a cut-off tool or scraper that makes the process almost idiot-proof, and I'd like a bit of idiot-proofing.

Friday, December 1, 2017

New Lathe

I spent all my meagre savings on a small wood-turning lathe for myself. It's pretty good for the price; a decently solid cast-iron construction that gives minimal vibration, and a 5-speed pulley system. The maximum distance between centres is about 420mm, so maybe just long enough to turn a chair leg on — there's an extension available for the bed though, which I may invest in at a later date if I find I need it. The only thing about it that I'm not that impressed with is the tool rest, which is very short, only 150mm (6") long. That will need to be addressed at some stage.

I enjoyed turning when I did it at 'tech, but I've done very little of it, and none at all for years, so what skills I had are now very, very rusty. It's going to take a bit of practice to get my hand back in.

My first very modest practice piece is this awl handle, made from a scrap of oak. The blade is an old 3mm drill bit shank.

Oak is a bit mixed as a turning wood. It's hard enough to cut crisply, but it has a fairly open grain, so the surface never looks as smooth and clean from the knife as fruit woods like apple or cherry. However, that's what I've got, so that's what I'm practicing on.

I enjoyed turning when I did it at 'tech, but I've done very little of it, and none at all for years, so what skills I had are now very, very rusty. It's going to take a bit of practice to get my hand back in.

My first very modest practice piece is this awl handle, made from a scrap of oak. The blade is an old 3mm drill bit shank.

Oak is a bit mixed as a turning wood. It's hard enough to cut crisply, but it has a fairly open grain, so the surface never looks as smooth and clean from the knife as fruit woods like apple or cherry. However, that's what I've got, so that's what I'm practicing on.

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

Mitre Saw Wheely-Stand Thing

I've had my mitre saw clamped to a folding workbench thingy (basically a cheaper version of the Black & Decker Workmate) for years. That was fine, but it was troublesome to shift around, and in my rather cramped little workshop I need to be able to shift things around so that they don't interfere with each other when I'm trying to use them.

So, I made this stand out of el-cheapo treated framing timber and some unexpectedly expensive locking castors. It doesn't look like much, but it's sold as a rock, and it gave me lots of practice at cutting mortice & tenon joints, bridle joints and lap joints.

We have bamboo growing in our garden, and I thought I'd use some as railings for the upper shelf, to stop things being pushed out the back or falling out the sides. Bamboo is good for that sort of use, as it's both thin and strong, and it will get stronger as it seasons. The down-side to it is that nature is distressingly imprecise in its sizing, and I had to do quite a bit of searching to get canes that were all within a size range that would fit my available drill holes.

As a side-effect of all this, I got my clamps a bit more organised and accessible. Next, I'll have to get a concrete pad under where the saw usually stands — at the moment it's sitting on various bits of wood spanning the rotten boards underneath, which isn't ideal.

So, I made this stand out of el-cheapo treated framing timber and some unexpectedly expensive locking castors. It doesn't look like much, but it's sold as a rock, and it gave me lots of practice at cutting mortice & tenon joints, bridle joints and lap joints.

We have bamboo growing in our garden, and I thought I'd use some as railings for the upper shelf, to stop things being pushed out the back or falling out the sides. Bamboo is good for that sort of use, as it's both thin and strong, and it will get stronger as it seasons. The down-side to it is that nature is distressingly imprecise in its sizing, and I had to do quite a bit of searching to get canes that were all within a size range that would fit my available drill holes.

As a side-effect of all this, I got my clamps a bit more organised and accessible. Next, I'll have to get a concrete pad under where the saw usually stands — at the moment it's sitting on various bits of wood spanning the rotten boards underneath, which isn't ideal.

Wednesday, November 22, 2017

What I Did Today

This afternoon I shifted a whole lot of wood and crap so I could shift some drawers so I could shift some bins so I could shift my mitre saw so I could shift those drawers again so I can use my table saw without banging bits of wood into things.

For a brief moment I marvelled at the unexpected amount of space I had.

Then I shifted all the wood back in again, which filled up most of that free space, and I realised that most of it is just rubbish so I'll have to go through it and start chucking most of it into the firewood pile.

And that's what I did today. Now I'm drinking cold beer, which is better.

(At some point I'm going to have to lay some more concrete so I can shift a workbench so I can shift my bandsaw to a more usable position, but not just yet. Not just yet.)

For a brief moment I marvelled at the unexpected amount of space I had.

Then I shifted all the wood back in again, which filled up most of that free space, and I realised that most of it is just rubbish so I'll have to go through it and start chucking most of it into the firewood pile.

And that's what I did today. Now I'm drinking cold beer, which is better.

(At some point I'm going to have to lay some more concrete so I can shift a workbench so I can shift my bandsaw to a more usable position, but not just yet. Not just yet.)

Monday, November 20, 2017

Yet Another Stool

I made another stool, this time out of some fairly dodgy, knotty white oak off-cuts. I had to work hard to get some decent lengths out of them, but persistence paid off in the end.

Our stool supply is outstripping the number of bums available to sit on them in normal daily life, but they'll come in handy for perching guests on.

I made many, many mistakes in building this. Perhaps I may learn from them, but who knows?

Our stool supply is outstripping the number of bums available to sit on them in normal daily life, but they'll come in handy for perching guests on.

I made many, many mistakes in building this. Perhaps I may learn from them, but who knows?

Tuesday, November 14, 2017

Stool Sample

I had a macrocarpa plank that was getting in the way, so I turned it into this stool.

For some reason it seems to me that it has a somewhat ecclesiastical feel, probably because of the scallops and what-not.

I like working with macrocarpa, but I can't say I'm especially fond of the knots. They tend to be dead knots too, so they fall out.

The stool is 600mm long by about 450mm high, a very comfortable sitting height for me. It's long enough for two people to sit on, as long as they're two very friendly people.

For some reason it seems to me that it has a somewhat ecclesiastical feel, probably because of the scallops and what-not.

I like working with macrocarpa, but I can't say I'm especially fond of the knots. They tend to be dead knots too, so they fall out.

The stool is 600mm long by about 450mm high, a very comfortable sitting height for me. It's long enough for two people to sit on, as long as they're two very friendly people.

Tuesday, November 7, 2017

Router Plane Revisited

I went back to the oak router plane I made a while ago and added some handles. It worked OK without them, but they give me a bit more control and it's easier on the hands this way. They're just a pair of tawa drawer-pulls.

Because its depth adjustment is by tap-and-hope rather than by means of a screw thread, it's a bit tricky to use with the precision of my Stanley or Record routers, but nevertheless it's pretty smooth and easy to use once you get used to its little quirks.

I'm using Veritas cutters in it, and though they're excellent cutters, they've introduced a complication.

As you can see, the back of the cutter curves forward towards the sole — I'm not sure why, but probably just as a side-effect of the tool's production when they're bent into shape. Anyway, the effect of this is that if the cutter is set to too shallow a depth, when the eye-bolt is tightened, it engages over the curved section and cants the cutter forward, and the edge of the blade is suddenly much deeper than one might have expected.

I have a couple of ideas for ameliorating this issue.

The first is to add a sleeve, anchored to the top of the router, through which the shaft of the blade runs. That should help some, and it's the most straightforward solution, but it won't entirely eliminate the problem because it will have to be fractionally loose on the shaft to allow the cutter's depth to be adjusted at all, and any slack will still allow the cutter to cant forward ever so slightly when it comes under pressure from the eye-bolt.

The second is to cut out the existing eye-bolt housing entirely, and glue in a new block in which a new housing is cut that will engage higher on the shaft of the cutter. I'd say, for safety's sake, the eye-bolt really needs to be engaging at least 10 mm higher up the shaft of the blade. That's a pretty major bit of surgery, and it would probably be quicker and easier just to make a whole new tool, taking into account what I've learned from this one.

Part Two

Part One

Because its depth adjustment is by tap-and-hope rather than by means of a screw thread, it's a bit tricky to use with the precision of my Stanley or Record routers, but nevertheless it's pretty smooth and easy to use once you get used to its little quirks.

I'm using Veritas cutters in it, and though they're excellent cutters, they've introduced a complication.

As you can see, the back of the cutter curves forward towards the sole — I'm not sure why, but probably just as a side-effect of the tool's production when they're bent into shape. Anyway, the effect of this is that if the cutter is set to too shallow a depth, when the eye-bolt is tightened, it engages over the curved section and cants the cutter forward, and the edge of the blade is suddenly much deeper than one might have expected.

I have a couple of ideas for ameliorating this issue.

The first is to add a sleeve, anchored to the top of the router, through which the shaft of the blade runs. That should help some, and it's the most straightforward solution, but it won't entirely eliminate the problem because it will have to be fractionally loose on the shaft to allow the cutter's depth to be adjusted at all, and any slack will still allow the cutter to cant forward ever so slightly when it comes under pressure from the eye-bolt.

The second is to cut out the existing eye-bolt housing entirely, and glue in a new block in which a new housing is cut that will engage higher on the shaft of the cutter. I'd say, for safety's sake, the eye-bolt really needs to be engaging at least 10 mm higher up the shaft of the blade. That's a pretty major bit of surgery, and it would probably be quicker and easier just to make a whole new tool, taking into account what I've learned from this one.

Next Day:

I added a collar to restrain the forward movement of the cutter when the eye-bolt is tightened, and it works well. It's made out of a 100mm (4") nail.

It looks a bit unsightly, I admit, but it does the job, and as an added bonus it ensures the cutter sets square to the cut. It can't be seen from this angle, but there's a vertical groove in the body of the router that ensures that the shaft is square vertically.

As I suspected, it doesn't eliminate the issue completely, as it has to be loose enough to allow the cutter shaft to move up and down, but the unwanted movement when the cutter is set shallow is now minimal, and much easier to compensate for.

Part Two

Part One

Friday, October 27, 2017

Mortise Gauges

I have several mortise gauges. The marking, or mortise, gauge is an incredibly useful tool; it would be possible to get by without one, but it would make one's woodworking life a lot more difficult.

If you don't know what a marking gauge is, it's used to scribe a line, or in the case of a mortise gauge a pair of lines, accurately relative to the edge of a piece of wood. What you do with it is set the block on the shaft at the distance you want the line, and then run the block along the edge of the wood so that the pin (or pins) in the shaft scores a line.

The top one is the first one I ever bought, and the simplest. It's made of beech, manufactured to quite decent tolerances, but it's not that easy to use as a mortise gauge because the secondary mortise pin is free-sliding, which means that you have to hold several things in place at once before tightening it up. It can often take several tries to get everything properly spaced, relative to each other. However, as a simple marking gauge (just using the single-pin side) it's great. I've modified it very slightly by re-shaping the pins from a conical section to spear-pointed triangles, so they cut the fibres of the wood rather than crushing them — this results in a much finer, more accurate line, but being so fine it can be difficult to see. especially in timber with a pronounced grain like oak.

The middle one I was given as a birthday present some years ago. It's quite old, and very well made from rosewood with brass inlays. It has a screw adjustment in the shaft for setting the mortise width, so it's a lot easier to be accurate when setting the relative positions of the block and the two mortise pins. Its only issue is that, being so old, it's been used a lot, and the pins have been sharpened and resharpened so much that they're mere nubbins. They could be replaced, but I'm not really confident enough of my skills to try it — it's not a straightforward disassembly job, and I fear that I might destroy it in the attempt.

The bottom one is one that I just bought by mail-order. It wasn't expensive, about twenty bucks or so, but it should see me out. It's made of Malaysian ebony with good, chunky brass anti-wear inserts on the face of the block. Like my rosewood one, it has a screw adjustment for the mortise pins

It has (or had) one significant issue though: the hole in the block had been machined too large, so the shaft rode quite sloppily in it. That would mean that you couldn't guarantee that everything was square when tightened up.

I fixed that by adding a pair of copper shims, one on either side of the shaft, to tighten everything up. You can see their ends folded around the face of the block (there's a similar flange at the back) to hold them in place. I cut a shallow recess in the face so that the shim rests below the surface of the block; that just ensures that it doesn't accidentally ride against your work-piece and send your line off its proper path.

I'll probably re-shape the pins the same way I've done on my beech gauge, but I'll give it some use first to see if that's really warranted.

If you don't know what a marking gauge is, it's used to scribe a line, or in the case of a mortise gauge a pair of lines, accurately relative to the edge of a piece of wood. What you do with it is set the block on the shaft at the distance you want the line, and then run the block along the edge of the wood so that the pin (or pins) in the shaft scores a line.

The top one is the first one I ever bought, and the simplest. It's made of beech, manufactured to quite decent tolerances, but it's not that easy to use as a mortise gauge because the secondary mortise pin is free-sliding, which means that you have to hold several things in place at once before tightening it up. It can often take several tries to get everything properly spaced, relative to each other. However, as a simple marking gauge (just using the single-pin side) it's great. I've modified it very slightly by re-shaping the pins from a conical section to spear-pointed triangles, so they cut the fibres of the wood rather than crushing them — this results in a much finer, more accurate line, but being so fine it can be difficult to see. especially in timber with a pronounced grain like oak.

The middle one I was given as a birthday present some years ago. It's quite old, and very well made from rosewood with brass inlays. It has a screw adjustment in the shaft for setting the mortise width, so it's a lot easier to be accurate when setting the relative positions of the block and the two mortise pins. Its only issue is that, being so old, it's been used a lot, and the pins have been sharpened and resharpened so much that they're mere nubbins. They could be replaced, but I'm not really confident enough of my skills to try it — it's not a straightforward disassembly job, and I fear that I might destroy it in the attempt.

The bottom one is one that I just bought by mail-order. It wasn't expensive, about twenty bucks or so, but it should see me out. It's made of Malaysian ebony with good, chunky brass anti-wear inserts on the face of the block. Like my rosewood one, it has a screw adjustment for the mortise pins

It has (or had) one significant issue though: the hole in the block had been machined too large, so the shaft rode quite sloppily in it. That would mean that you couldn't guarantee that everything was square when tightened up.

I fixed that by adding a pair of copper shims, one on either side of the shaft, to tighten everything up. You can see their ends folded around the face of the block (there's a similar flange at the back) to hold them in place. I cut a shallow recess in the face so that the shim rests below the surface of the block; that just ensures that it doesn't accidentally ride against your work-piece and send your line off its proper path.

I'll probably re-shape the pins the same way I've done on my beech gauge, but I'll give it some use first to see if that's really warranted.

Wednesday, October 25, 2017

Stool

Today I gave my DeWalt thicknesser its very first outing on its shiny new wheely-stand, and used it to plane down some bits of macrocarpa that I had lying around from another project that never got off the ground.

I put together this sitting-stool, which is shown here having just had its first coat of linseed oil. It will most likely end up being another piece of outdoor furniture; macrocarpa is a good timber for that.

Just as an aside: when I was a kid, I thought macrocarpa was a Maori word, not Latin. I thought it was makorokaporo. I have no idea what, if anything, makorokaporo would mean though.

I put together this sitting-stool, which is shown here having just had its first coat of linseed oil. It will most likely end up being another piece of outdoor furniture; macrocarpa is a good timber for that.

Just as an aside: when I was a kid, I thought macrocarpa was a Maori word, not Latin. I thought it was makorokaporo. I have no idea what, if anything, makorokaporo would mean though.

Saturday, October 21, 2017

Tanto

In my scrap pile today I found a very curly bit of oak. It has grain going about seventeen different ways at once, and was impossible to work with any of the bladed tools I own, so I made this wooden tanto for aikido training entirely with rasps and files.

It's actually a pretty shitty piece of timber for almost any purpose, but I really like the chaotic figure of the grain.

It's actually a pretty shitty piece of timber for almost any purpose, but I really like the chaotic figure of the grain.

Monday, October 16, 2017

Wooden Router Plane - Finis

I finished off shaping my wooden router plane, and gave it a few coats of shellac and a spot of wax.

It works fine, but it's not going to be taking the place of my trusty Record or Stanley routers any time soon. It'll be purely an emergency backup extra router, in case I should need one.

Part Three

Part One

It works fine, but it's not going to be taking the place of my trusty Record or Stanley routers any time soon. It'll be purely an emergency backup extra router, in case I should need one.

Part Three

Part One

Saturday, October 14, 2017

Making a Wooden Router Plane

This may not look like anything much, but it's actually a fully functional router plane.

Admittedly, it's not a very beautiful router plane just yet, but it works as one, which is the important thing. It has some shaping to be done as yet, now that I know it works as expected, and I also want to add a couple of tee-nuts so that I can mount a grooving fence to it.

The cutter is from Veritas, and is the same format as that for the Stanley No.70 or Record No.71 planes. It's held in place by a ¼" threaded eye-bolt which passes through the body of the router to a wing-nut at the back.

The wing-nut is functional, but uncomfortable, and I'd like to replace it with a knurled thumb-nut at some stage.

I've learned a thing or two from this so far, and I may (or may not) make another.

Part Two

Part Three

Admittedly, it's not a very beautiful router plane just yet, but it works as one, which is the important thing. It has some shaping to be done as yet, now that I know it works as expected, and I also want to add a couple of tee-nuts so that I can mount a grooving fence to it.

The cutter is from Veritas, and is the same format as that for the Stanley No.70 or Record No.71 planes. It's held in place by a ¼" threaded eye-bolt which passes through the body of the router to a wing-nut at the back.

The wing-nut is functional, but uncomfortable, and I'd like to replace it with a knurled thumb-nut at some stage.

I've learned a thing or two from this so far, and I may (or may not) make another.

|

| The cutter and eye-bolt |

|

| The wing-nut |

Part Three

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

Cunning Dovetail Jig

This may not look like much, but in fact it's an amazingly useful and cunning dovetailing jig that makes cutting dovetails a piece of cake. It's a variation on a jig developed by Paul Sellars.

One of the crucial things to get well-fitting dovetails is getting your cuts dead square, which is especially tricky on very thin stock. I've been making a bunch of small boxes out of 8mm thick pine, and 8mm doesn't give you much leeway to gauge your accuracy visually.

The thick base of this jig allows you to get your cuts square every time. Its been marked and cut with one raked cut for a side of the dovetail, and one horizontal cut, for a shoulder. In this instance I only need one tail, but it can be easily expanded for multiple tails.

The piece to be cut is put into the jig, hard up against the side piece and hard up against the top registration peg(s).

Then the saw is offered into the dovetail cut in the jig, and the first cut is made.

The piece is then flipped over, and the cut on the other side of the tail is made the same way.

Again, the piece is flipped over and the opposite cut is made the same way.

There are a couple of changes I'd make for future versions.

One of the crucial things to get well-fitting dovetails is getting your cuts dead square, which is especially tricky on very thin stock. I've been making a bunch of small boxes out of 8mm thick pine, and 8mm doesn't give you much leeway to gauge your accuracy visually.

The thick base of this jig allows you to get your cuts square every time. Its been marked and cut with one raked cut for a side of the dovetail, and one horizontal cut, for a shoulder. In this instance I only need one tail, but it can be easily expanded for multiple tails.

NOTE: The observant will note that there are actually two shoulder cuts, but I realised that by putting a registration peg out in the middle of the tail I'd only need the one.

The piece to be cut is put into the jig, hard up against the side piece and hard up against the top registration peg(s).

Then the saw is offered into the dovetail cut in the jig, and the first cut is made.

The piece is then flipped over, and the cut on the other side of the tail is made the same way.

Note: I'm not left-handed; this is a posed shot for the camera.Next, the whole lot is turned sideways in the vice, and the first shoulder cut is made in the same manner.

Again, the piece is flipped over and the opposite cut is made the same way.

Note: that left-hand cut is one I included before I realised that a registration peg in the middle of the tail would give more accurate symmetry than relying on allowing for the depth of the shoulder with the original corner peg.I didn't time my work, but I'd be surprised if it took more than four or five minutes to complete each piece, with guaranteed accuracy. It would be longer of course if you're cutting multiple tails, but it's still much faster and more reliable than doing it all by eye.

There are a couple of changes I'd make for future versions.

- I'd make the jig back-plate a bit wider, say about 25mm wider than the work piece, so that the saw starts its shoulder cut more reliably square. On this one, there's only a couple of millimetres from the edge of the piece to the edge of the jig, and though it worked OK, more depth would be better.

- The top registration peg in the corner isn't really necessary. A single peg that sits in the middle of the piece's tail is adequate to ensure that everything is properly registered for cutting.

Tuesday, October 10, 2017

Friday, October 6, 2017

Saw Conversion Complete (mostly)

The conversion of my cheap gents' saw into a rather nice dovetail saw is pretty much complete.

It's now completely usable, and it cuts very nicely with a good thin kerf.

Alas, it's still moderately hideous from its left-hand side until I can figure out a decent way to hide the captive square bolts. They don't affect the saw's functionality in any way, but they're aesthetically unpleasing.

Thursday, October 5, 2017

Saw Conversion

I have an inexpensive gents' saw that I'm converting into a pistol-grip dovetail saw. I'll have to remove the saw's handle, cut off the tang and reshape the plate slightly, and then mount it into the new handle I'm in the process of shaping from a piece of 25mm thick oak I had lying around.

The existing saw is OK, though not great. The steel is decent and it cuts well, but its back-spline is a little light. Ideally I'd like to change that for a good stiff, heavy brass one, but I'm not sure that I'm capable. For the moment it can stay with the existing spline; I can always swap it out at a later date with only minor surgery to the new handle.

This is more or less how it will look when it's assembled. Of course, the grip will be shaped so that it's a lot more comfortable to hold.

One thing that's troubling me is the pair of nuts and bolts that should hold the plate to the handle. Traditionally they should be brass split-nuts, in which the bolt (or rather, machine screw) part of the pair screws into a threaded, capped tube. This gives the assembly a very neat look, but as far as I can find they're just not available anywhere in New Zealand except by cannibalizing some from an old saw. I can get some from overseas, but they're quite expensive in themselves, and the postage being demanded by the vendors is eye-watering — one mob in the UK wants £45 in addition to the cost of the fixings themselves!

Well, they're not essential; I want to use them mostly for aesthetic reasons. It would be nice to have some though, not least because I have some missing from some of my other saws that I'd like to replace.

Later....

I finished the shaping of the handle, and gave it a single coat of oil just to seal it.I drilled a couple of small guide holes where the screws will eventually go; there's no point in going any further with them until I know exactly what hardware I've got for them.

Friday, September 29, 2017

Registration and Separations

I've figured out a way of getting properly registered colour separations (and, eventually, prints).

I've built a frame on a piece of MDF which closely surrounds the block on three sides. Outside that frame are registration tabs to set the paper into, so the paper and block are always in exactly the same place, relative to each other. All the blocks are precisely the same size, so it works for all of them.

The frame around the block is the same thickness as the MDF I've cut the block from, which means that there's a support for the baren to run on to — that helps to keep it out of the voids, and it also means that it's less likely to shift the block by pressing against an outside edge. There's a floating piece, not attached, that I put across the right-hand edge after the block is in place for the same purpose.

The colour block guide prints are created by an offset printing process. The key block (the one in the frame in this photo) is printed on to a sheet of mylar, registered in the paper registration tabs. Then it and the key block are removed, one of the colour blocks put into the frame, and the mylar replaced against the registration tabs, and rubbed down against the fresh block with a rubber brayer (roller). That transfers a reversed image of the key block in perfect registration, and I can use that image to guide me in cutting the colour block.

I've put up a cheap portable washing line in my workshop that I can use for drying prints. These ones are on A3 sheets, and I figure I could get about 30 up there before they started to interfere with my printing area. I'm unlikely to be doing any large runs, so that should be plenty.

I've built a frame on a piece of MDF which closely surrounds the block on three sides. Outside that frame are registration tabs to set the paper into, so the paper and block are always in exactly the same place, relative to each other. All the blocks are precisely the same size, so it works for all of them.

The frame around the block is the same thickness as the MDF I've cut the block from, which means that there's a support for the baren to run on to — that helps to keep it out of the voids, and it also means that it's less likely to shift the block by pressing against an outside edge. There's a floating piece, not attached, that I put across the right-hand edge after the block is in place for the same purpose.

The colour block guide prints are created by an offset printing process. The key block (the one in the frame in this photo) is printed on to a sheet of mylar, registered in the paper registration tabs. Then it and the key block are removed, one of the colour blocks put into the frame, and the mylar replaced against the registration tabs, and rubbed down against the fresh block with a rubber brayer (roller). That transfers a reversed image of the key block in perfect registration, and I can use that image to guide me in cutting the colour block.

I've put up a cheap portable washing line in my workshop that I can use for drying prints. These ones are on A3 sheets, and I figure I could get about 30 up there before they started to interfere with my printing area. I'm unlikely to be doing any large runs, so that should be plenty.

Tuesday, September 26, 2017

New-Model Baren (Mk.II & III)

|

| At top, Baren Mk.I, the one I've been using up until now On the right, Baren Mk.II (8mm cabochons), and to the left, Mk.III (12mm). |

The disks are 120mm in diameter, cut from 3mm hardboard. Hardboard is more hard-wearing and less vulnerable to water than MDF; it's not likely that these will ever get significantly wet, but better safe than sorry. The cabochons are glued to the disks with 24-hour cure epoxy resin (so they won't be ready for use until tomorrow at the earliest).

Both of the new ones are wider and flatter than the first one I made, which should make it less likely that they'll push paper down into the voids of a block where excess ink can often be found. The 8mm beads make for the flattest surface of course, with the largest number of contact points; I suspect that will also make it the hardest, physically, to use, as it will require more strength to keep all those points in firm contact with the paper surface. The proof of the pudding will be, as they say, in the eating. I won't know for sure until I actually start using them.

The 8mm beads have been laid out in a regular grid, while the 12mm beads were laid out in decreasing concentric circles. What difference (if any) that will make, I don't know; I'd like to try the less regular layout with the smaller cabochons, but I'll have to order some more in that case as I've used up almost my entire supply on this one.

Friday, September 22, 2017

Linocut

|

| That gouge is a very shitty gouge. Really, really shitty. |

Like lino, it's not great at reproducing very fine detail, but then if I want that I'll use wood.

It's not without its faults though. It repels water, so I can't draw directly on to the block with brush and indian ink as is my preference. Nor does it accept solvent transfer from a photocopy or laser print. A pencil line is quite indistinct against the green or blue background. I can draw on it with a Sharpie, so at least there's that.

I have some 75mm (3") Speedball soft rubber brayers, and I like them, but they're rather too narrow for me. I'd like some at least twice that width; the smaller ones have a tendency to fall into voids and leave ink where it's not wanted, so open areas have to be cut a bit deeper than would otherwise be necessary to keep them from printing.

My glass-bead baren, though otherwise excellent, is also a bit small, and the individual cabochons a little large. I'm waiting on some smaller glass cabochons, and when they arrive I'll make a wider, flatter one.

Saturday, September 9, 2017

Friday, September 8, 2017

The Proof Is Out There

|

| The block |

|

| The first proof |

I was originally planning to cut away the blank background areas completely, to eliminate the chance of any accidental ink contamination, but then I realised that would make registration placement quite difficult. So instead, I carved them away quite deeply so that the brayer (ink roller) doesn't touch them. I'll probably also give them a couple of coats of gloss varnish, so that if I do get ink in those areas I can just wipe it away.

The first proof (right) was pretty successful. There are a couple of areas that could do with a bit of extra cutting, but overall I'm fairly happy with it.

I can see that I'm going to have to be quite careful with the baren at the ends of the block — you can see a faint patch at bottom right where I skipped over it a bit.

Next up, I shall build a registration frame and start working out the colour blocks.

Thursday, September 7, 2017

Block Cutting

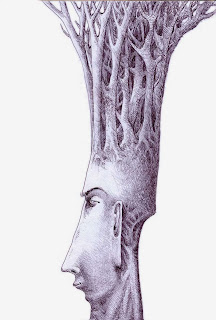

I'm cutting my first block in quite some considerable time, and my hands and neck are cramping up something awful. This is the key block; I'm thinking the finished print will be in three or maybe four colours, so of course blocks will have to be carved for each of them as well.

I'm using MDF, which isn't the best material in the world for block making, but it has some advantages. It's cheap and easily available, and it has no grain, which makes carving it a lot more like linocut than woodcut — your knife or gouge isn't going to be deflected by an unexpectedly hard and twisty bit of grain. However, it's rather fibrous, and if your tools aren't scalpel-sharp it tends to tear. It's pretty hard on tool edges too, so you need to be sharpening fairly often.

The image is one that I drew a few years ago, in ball-point pen.

I did a solvent transfer of a laser print of it on to the MDF, and then over-drew it with brush and Indian ink — I find that a brush drawing works quite well as a cutting guide, as I can't get too finicky about detail that I'd never be able to cut. For an image like this, the brush line changes the character of the image somewhat, but I like that; there seems little point to me in trying to force one medium into replicating another.

The small print you see in the main image is just a quickie I took early on in the cutting to see how the cutting will reproduce. That ink should be red, but it's been sitting in its tube so long that it's separated out, and despite all the kneading and massaging of the tube I could do, it stubbornly persists in squirting out mainly its chrome yellow base. I did the test print in a colour other than black because I wanted to still be able to see my ink lines afterwards.

I'm using MDF, which isn't the best material in the world for block making, but it has some advantages. It's cheap and easily available, and it has no grain, which makes carving it a lot more like linocut than woodcut — your knife or gouge isn't going to be deflected by an unexpectedly hard and twisty bit of grain. However, it's rather fibrous, and if your tools aren't scalpel-sharp it tends to tear. It's pretty hard on tool edges too, so you need to be sharpening fairly often.

The image is one that I drew a few years ago, in ball-point pen.

I did a solvent transfer of a laser print of it on to the MDF, and then over-drew it with brush and Indian ink — I find that a brush drawing works quite well as a cutting guide, as I can't get too finicky about detail that I'd never be able to cut. For an image like this, the brush line changes the character of the image somewhat, but I like that; there seems little point to me in trying to force one medium into replicating another.

The small print you see in the main image is just a quickie I took early on in the cutting to see how the cutting will reproduce. That ink should be red, but it's been sitting in its tube so long that it's separated out, and despite all the kneading and massaging of the tube I could do, it stubbornly persists in squirting out mainly its chrome yellow base. I did the test print in a colour other than black because I wanted to still be able to see my ink lines afterwards.

Friday, September 1, 2017

Baren Test

I gave my glass-bead baren its first test outing today. I used water-soluble Flint relief printing ink, applied to a roughly 120mm square MDF block with a rubber brayer.

This one is one very thin, smooth note paper, and it was pretty easy to get a fairly clean, sharp impression. I need to pay close attention to keeping the paper in place though; the first one I did moved about a bit under the rotational thrust of the baren, but it's not really difficult to keep it still if I pay attention.

This one is on fairly heavy printmaking paper — I don't know the manufacturer — about 280-300 gsm, I'd guess.

The impression is not as clean as on the thinner, smoother paper, which is not unexpected, but it's not too bad. It's worst at the bottom of the print, which I think is because I was a bit uneven in my rubbing pressure.

What I've learned from this very brief test is that the glass beads work very well as a baren surface, moving smoothly and easily over the paper surface, and it's easy to get a good amount of pressure without having to grunt and strain. However, I think it would work better with more, smaller beads, more closely spaced, so I'll see what I can find and make a second one.

This one is one very thin, smooth note paper, and it was pretty easy to get a fairly clean, sharp impression. I need to pay close attention to keeping the paper in place though; the first one I did moved about a bit under the rotational thrust of the baren, but it's not really difficult to keep it still if I pay attention.

This one is on fairly heavy printmaking paper — I don't know the manufacturer — about 280-300 gsm, I'd guess.

The impression is not as clean as on the thinner, smoother paper, which is not unexpected, but it's not too bad. It's worst at the bottom of the print, which I think is because I was a bit uneven in my rubbing pressure.

What I've learned from this very brief test is that the glass beads work very well as a baren surface, moving smoothly and easily over the paper surface, and it's easy to get a good amount of pressure without having to grunt and strain. However, I think it would work better with more, smaller beads, more closely spaced, so I'll see what I can find and make a second one.

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

Baren

|

| The components |

|

| All the bits together |

|

| It looks kind of delicious, don't you think? |

The cabochons are glued to the hardboard with epoxy. I've used the 24-hour cure super-strength stuff, but mainly for its extended working time rather than for its mechanical properties.

The glass cabochons themselves aren't precisely sized, which would make getting a perfectly level surface difficult (or impossible) if I glued them directly to the hardboard disc. So, instead I laid them out flat-side-up on this silicone baking sheet, added a blob of epoxy to each one, and then laid the disc down on top of them. The unevenness of the cabochon thickness is taken up by the epoxy resin, so it no longer matters that they're all subtly different.

Conveniently, the sheet has these concentric rings printed on it, which made it a simple matter to keep everything centred.

It would be usable in its present state (once the glue has cured properly), but I intend to add a shallow wooden dome to it, both to make it easier to hold, and also to ensure that my hand pressure is being distributed evenly across the whole face of the baren. I'll also be able add a hand-strap, which means that I won't have to divert any energy to just holding on to the thing.

I'm getting really impatient to see how well it works. I must hold my enthusiasm in check until everything is properly dry.

A few days later....

|

| Shellacked oak hand-pad |

|

| Delicious-looking glass cabochons, looking like glacé cherries. |

I've finished it off now, with the addition of a fairly hefty shellacked oak hand-pad. The whole thing is about 100mm in diameter.

I've only given it one outing as yet, and a fairly perfunctory one at that, but it was sufficient to give me an idea as to how to improve it. These cabochons are 20mm in diameter, and I think it would work better with more and smaller beads. To that end, I've ordered some 8mm and 12mm cabochons, and when they arrive I'll make a couple more and see how they compare.

I'm feeling quite optimistic about it.

So, now I shall have to get on to cutting some blocks, and getting some decent light-weight paper to print on — the baren works OK with heavier paper, but it's definitely more hard work, and the printing isn't quite as crisp.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)